17. Regular Expressions for JavaScript Explained

What is a Regular Expression?

They are patterns used to match character combinations in Strings. It is a generic feature and has been implemented in many languages. All languages have their own Regular Expression engines built in to process them. Regular Expressions should be written with caution as they can cause severe performance impact to the code/application and end up consuming significant amount of CPU searching for a pattern.

In JavaScript Regular Expressions are objects of the type RegExp.

There are specific functions present as part of the built-in String and RegExp objects which takes these regular expressions as inputs to run comparisons.

String - match(), matchAll(), replace(), search(), split()

RegExp - exec(), test()

How do we create Regular Expression in JavaScript?

There are 2 ways of doing that:

- Using a Regular Expression Literal - This can be done by enclosing the pattern string in-between slashes. This is compiled to regular expression at the time the script is loaded. Which means if the expression remains constant using this method will lead to better performance.

var regExp1 = /ab+c/; - Using constructor function of

RegExpobject - This compiles the expression at the runtime and should be used when the expression is likely to change or when the expression to be used is not known at the authoring time of the code, such as when it's an user input.var regExp2 = new RegExp('ab+c');String.prototype.match()method to check the behavior of the regular expression.

What are Regular Expressions composed of?

They are composed of simple characters like a, b, c, 1, 2, etc, and special characters like \, * etc.

Simple Patterns: This kind of expression pattern matches the character combination where an exact match is found in sequence, i.e. all characters together and in that order. For example:

var re1 = /abc/;

var testStr = " This string contains ABC , abc , Abc,AB and C";

console.log(testStr.match(re1));

/*output:

[ 'abc',

index: 28,

input: ' This string contains ABC , abc , Abc,AB and C' ]

*/

var testStr1 = "ABC";

console.log(testStr1.match(re1));//null

So when an exact match to the string "abc" is encountered in the same case the expression returns an array with some properties, else it returns null.

Special Characters Patterns: This is used where a more complicated sequence of expressions needs to be searched. Such expressions can be used to find more then one occurrence of a particular character, or a white space character etc. For example to search for a followed by 0 or more occurrences of b followed by c, we can write the expression as ab*c, where the * means 0 or more occurrences of a character.

The special characters used in Regular Expressions can be categorized as below:

- Assertions

- Character Classes

- Groups and Ranges

- Quantifiers

- Unicode property escapes

Let's see in details each of these:

Assertions

This includes matching boundaries, which indicate beginnings and endings of lines and words, and other patterns like look-ahead, look-behind and conditional expressions. Below are the two categories of assertions:

Boundary Type Assertions:

^- matches the beginning of an input. If the multi-line flag is set(//m) then it also matches characters after it encounters any line break character.

If multiple matches are found it returns the first occurrence.

NOTE: This character has a different meaning if it appears at the start of a group.var assertionString1 = "one string \nOne string \nown string"; var assertionRE1 = /^O/;//case senitive match by default var assertionRE2 = /^O/i;//case insensitive match var assertionRE3 = /^o/; var assertionRE4 = /^O/m;//multi-line search for "O" console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE1));//null - first line does not have "O" as first character, so returns null console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE2));//[ 'o', index: 0, input: 'one string' ] - return result as case-insensitive search is performed console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE3));//[ 'o', index: 0, input: 'one string' ] - first line has "o" as first character console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE4));//[ 'O', index: 12, input: 'one string \nOne string \nown string' ] - one of the lines(line 2) has "O" as the first character$- this matches the end of an input. If multi-line flag(//m) is set then it also matches characters before it encounters any line break character.

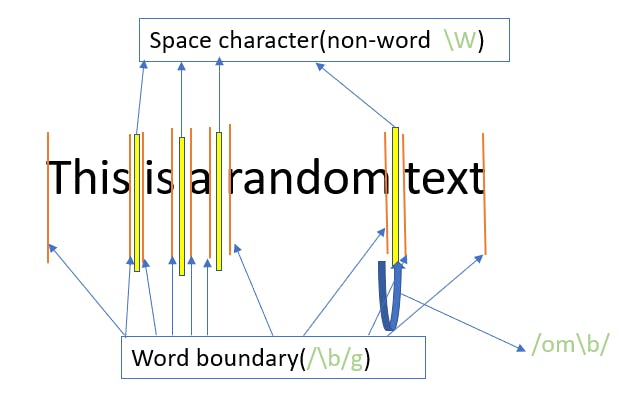

If multiple matches are found it returns the first occurrence.var assertionString1 = "big city\nbig citY\nbig city"; var assertionRE1 = /Y$/;//case senitive match by default var assertionRE2 = /Y$/i;//case insensitive match var assertionRE3 = /y$/; var assertionRE4 = /Y$/m;//multi-line search for "Y" console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE1));//null console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE2));//[ 'y', index: 25, input: 'big city\nbig citY\nbig city' ] console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE3));//[ 'y', index: 25, input: 'big city\nbig citY\nbig city' ] console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE4));//[ 'Y', index: 16, input: 'big city\nbig citY\nbig city' ]\b- this matches a word boundary. This mean the it will return a result when the matching pattern is not preceded by another word character(\w), like between a letter and a space. The matched word boundary is not included in the match as their length is zero./\w\b\w/will never match anything, because a word character can never be followed by both a non-word(\W- tabs, spaces, newline etc.) and a word character.var assertionString1 = "someone speak\nto me"; var assertionRE1 = /\bsome/; var assertionRE2 = /\bone/; var assertionRE3 = /\bspe/; var assertionRE4 = /\bto/; console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE1));//[ 'some', index: 0, input: 'someone speak' ] console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE2));//null console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE3));//[ 'spe', index: 8, input: 'someone speak' ] console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE4));//[ 'to', index: 14, input: 'someone speak\nto me' ] because \n is non-word character The above image illustrates when we apply a regex

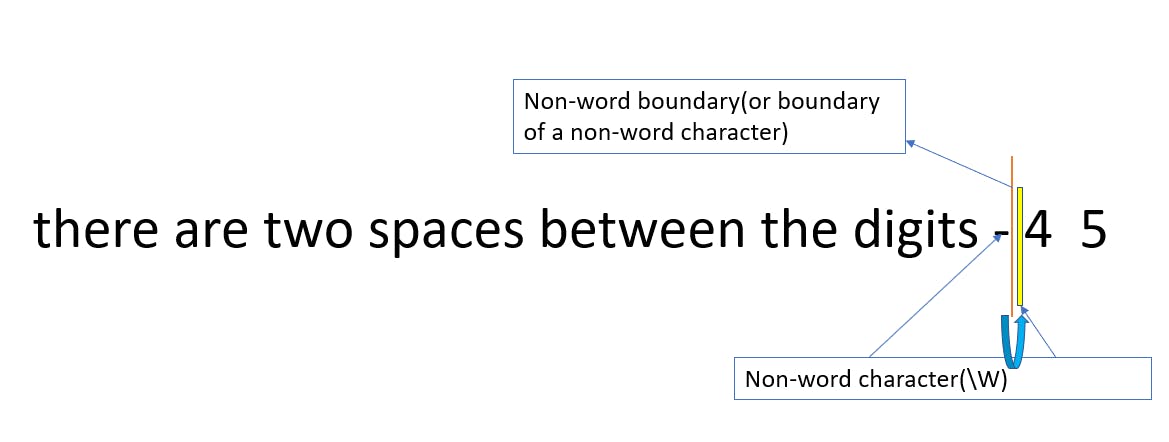

The above image illustrates when we apply a regex /om\b/on the above string, it tries to find the pattern "om", such that there exists a position or a word boundary(marked in orange above) whose left and right side contains characters are of different types(in above example the left side contains the character "m" which is a word character(\w) and right side contains the character " "(space) which is non-word character(\W).\B- matches a non-word boundary. This position is between 2 characters of the same type(either both words or both non-words), like between two letters or two spaces.var assertionString1 = "there are two spaces between the digits - 4 5" var assertionRE1 = /\Ba/; var assertionRE2 = /\B /; var assertionRE3 = /\Bare/; console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE1));//because "a" in spaces has a word character on either side /* [ 'a', index: 16, input: 'there are two spaces between the digits - 4 5' ] */ console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE2)); /* [ ' ', index: 41, input: 'there are two spaces between the digits - 4 5' ] */ console.log(assertionString1.match(assertionRE3));//nullassertionRE2has such result ? The below diagram explains it:

The regular expression was able to find a non-word boundary(boundary of a non-word character) whereon either side of it there are same types of characters, in this case both are non-word and the left side has a hyphen(

The regular expression was able to find a non-word boundary(boundary of a non-word character) whereon either side of it there are same types of characters, in this case both are non-word and the left side has a hyphen(-) and the right side has a space(" ").

Other Assertions:

- Lookahead assertion(

x(?=y)) - Matchesxonly ifxis followed byy. - Negative lookahead assertion(

x(?!y)) - Matchesxonly ifxis not followed byy. - Lookbehind assertion(

(?<=y)x) - Matchesxonly ifxis preceded byy. - Negative lookbehind assertion(

(?<!y)x) - Matchesxonly ifxis not preceded byy.var num = "1234576248486382974573"; var regex1 = /5(?=7)/; //find the first 5 suceeded by 7 var regex2 = /8(?!4)/; //find the first 8 not succeded by 4 var regex3 = /(?<=4)5/; //find the first 5 preceded by 4 var regex4 = /(?<!7)6/; // find the first 6 not preceded by 7 console.log(num.match(regex1));//[ '5', index: 4, input: '1234576248486382974573' ] console.log(num.match(regex2));//[ '8', index: 11, input: '1234576248486382974573' ] - this gives the position of second occurance of 8 which is the first 8 character in the string not followed by a 4. console.log(num.match(regex3));//["5", index: 4, input: "1234576248486382974573"] console.log(num.match(regex4));//["6", index: 12, input: "1234576248486382974573"

Character classes

This is used to distinguish between different types of characters, like digits and letters.

.- The dot has different interpretations under different circumstances.- It matches any single character except line terminators(

\n,\r,\u2028,\u2029) - Inside a character set the dot does not have any special meaning and matches a literal dot.

var str = "hey and hay sound similar"; var regex1 = /h.y/; var regex2 = /.ay/; console.log(str.match(regex1));//[ 'hey', index: 0, input: 'hey and hay sound similar' ] console.log(str.match(regex2));//[ 'hay', index: 8, input: 'hey and hay sound similar' ]

- It matches any single character except line terminators(

\d- Matches any digit. Equivalent to[0-9].\D- Matches a character that is not a digit. Equivalent to [^0-9].var str = "The first whole number is 0"; console.log(str.match(/\d/));//[ '0', inde x: 26, input: 'The first whole number is 0' ] console.log(str.match(/\D/));//[ 'T', index: 0, input: 'The first whole number is 0' ]\w- or as we have referred to as the word character. This include alphanumeric character from the basic Latin alphabet, including underscore. It is equivalent to[A-Za-z0-9_].\W- or as we have referred to as the non-word character. This includes all the characters that is not a word character. It is equivalent to[^A-Za-z0-9_]. Here the^stands for negation.console.log("_1".match(/\w/));//[ '_', index: 0, input: '_1' ] console.log("5.3".match(/\w/));//[ '5', index: 0, input: '5.3' ] console.log("cat".match(/\w/));//[ 'c', index: 0, input: 'cat' ] console.log("5.1".match(/\W/));//[ '.', index: 1, input: '5.1' ] console.log("5*1".match(/\W/));//[ '*', index: 1, input: '5*1' ]\s- Matches a single white space character including space, tab, form feed, line feed, carriage return and other Unicode spaces. It is equivalent to[\f\r\n\t\v\u00a0\u1680\u2000-\u200a\u2028\u2029\u202f\u205f\u3000\ufeff].\S- Matches a single non-white space character. It is equivalent to[^\f\n\r\t\v\u00a0\u1680\u2000-\u2000a\u2028\u2029\u202f\u205f\u3000\ufeff]\t- Matches a horizontal tab.\r- Matches a carriage return.\n- Matches a new line feed.\v- Matches a vertical tab.\f- Matches a form feed.[\b]- Matches a backspace.\0- Matches a NUL character.\cX- Matches a control character using caret notation , whereXstands for a letter from A-Z(corresponding to codepoints U+0001–U+001F). For example, /\cM/ matches "\r" in "\r\n".\xhh- Matches the character with the code hh (two hexadecimal digits).\uhhhh- Matches a UTF-16 code-unit with the value hhhh (four hexadecimal digits).\u{hhhh}or\u{hhhhh}- (Only when the u flag is set.) Matches the character with the Unicode value U+hhhh or U+hhhhh (hexadecimal digits).\-Used to escape the character after it. For example,/b/matches the literal characterbwhereas/\b/matches a word boundary. Similarly*is already having a special meaning in/a*/where it matches 0 or more occurrences of the charactera. So if we need to match*literally the we need to escape it as/a\*/.

Groups and Ranges

This is used to indicate groups and ranges of expression characters.

x|y- This is an OR condition that matches eitherxory.[xyz]or[a-c]- This signifies a character set and matches any one of the enclosed character. We can specify a range using hyphen(-), but if hyphen is the first/last character it will be treated as the literal character. It is possible to include the character class in a character set.console.log("hail Jesus, hail Mary".match(/Jesus|Mary/));//[ 'Jesus', index: 5, input: 'hail Jesus, hail Mary' ] console.log("1234xyz".match(/[x-z]/));//[ 'x', index: 4, input: '1234xyz' ] console.log("1234xyz".match(/[3-4]/));//[ '3', index: 2, input: '1234xyz' ] console.log("1234xyz".match(/[a-f]/));//null //console.log("1234xyz".match(/[z-x]/));//SyntaxError: Invalid regular expression: /[z-x]/: Range out of order in character class console.log("4hias89q3foin-".match(/[a-z-]/));//[ 'h', index: 1, input: '4hias89q3foin-' ] console.log("-4hias89q3foin".match(/[-a-z]/));//[ '-', index: 0, input: '-4hias89q3foin' ] console.log("\n\t\r\vA5*\t\u2028".match(/\w*/g));//[ '', '', '', '', 'A5', '', '', '', '' ] - since * is special character console.log("\n\t\r\vA5*\t\u2028".match(/\w\*/g));//[ '5*' ] - escape the * to search the literal[^xyz]or[x-z]- this signifies a negated/complemented character set. All features of this pattern are same as above character set, just that it searches for characters not provided in the character set.(x)- This is called as Capturing groups. This matchesxand remembers the match as numbered elements of the returned array. The count of the numbered elements in the returned array is equal to the number of groups(including distinct nested groups) present in the regular expression supplied for the match. Let us see a simple example.var str = "mooomoomooooomoooooomooomoomo"; var r = /(moo)(mooo)/; var mtch = str.match(r); /* [ 'moomooo', //mtch[0] 'moo', //mtch[1] 'mooo', //mtch[2] index: 4, input: 'mooomoomooooomoooooomooomoomo' ] */ console.log(mtch); console.log(mtch[0]);//moomooo console.log(mtch[1]);//moo console.log(mtch[2]);//mooomoofollowed bymooo. However the resulting returned array will have 2+1 = 3 numbered elements indexed frommtch[0]tomtch[2]. The data in these 3 indices are:mtch[0]- the entire part of string matched by the regular expressionmtch[1]- the part of string matched by the first capturing groupmtch[2]- the part of string matched by the second capturing group

If no match for these indices are found the value at these indices will beundefined.

Now the above example was not so useful in a real world scenario. Let us consider more realistic scenario where we can use this. We can use it to extract the various parts of an email. Now most commonly, all email have a particular format(the specification for email id is here ):local_part@domain.higher_domain

Now we can write a regular expression to extract all these 3 parts using the capturing group options as below:var myEmailId = "s_c_bose@ina.com" var extractEmailIdRegEx = /(\w+)@(\w+).(\w+)/; var emailPart = myEmailId.match(extractEmailIdRegEx); console.log(emailPart); /* [ 's_c_bose@ina.com', 's_c_bose', -- base part 'ina', -- domain name 'com', -- higher domain index: 0, input: 's_c_bose@ina.com' ] */var myEmailId = "s_c_bose@ina.com" var extractEmailIdRegEx = /(?<>\w+)@(\w+).(\w+)/; var emailPart = myEmailId.match(extractEmailIdRegEx); myEmailId = myEmailId.replace(emailPart[1], "xxxxxx");// xxxxxx@ina.com\n- This is a back reference. The value ofnis a positive integer and it represents one of the string matches from the capture group. Let us assume in some user input we want to validate whether the same email id is given twice as comma separated inputs or not, we can do the following:var email = "abc@def.com, abc@def.com"; var reg = /(\w+\@\w+\.\w+),\s\1/; console.log(email.match(reg));\1represent the same email id that was captured using the capture group.(?<name>x)- This is named capturing group. This is similar to capturing groups. So how is it different from capturing groups? If named capturing groups are used then in thegroupsproperty(whose value is an object) of the returned array new properties are added whose names are the group names specified in the regular expression. The angle bracket are part of the syntax.

Let us see the same email example in this context:var myEmailId = "s_c_bose@ina.com" var extractEmailIdRegEx = /(?<localPart>\w+)@(?<domainName>\w+).(?<higherDomainName>\w+)/; var emailPart = myEmailId.match(extractEmailIdRegEx); console.log(emailPart); /* [ 0: "s_c_bose@ina.com" 1: "s_c_bose" 2: "ina" 3: "com" index: 0 input: "s_c_bose@ina.com" groups: {localPart: "s_c_bose", domainName: "ina", higherDomainName: "com"} length: 4 ] */groupsobject.(?:x)- This is the syntax for non-capturing groups. It matchesxbut does not remember the match and hence the matched substring cannot be recalled or referenced at a later point. The below example showcases the difference between capturing and non-capturing groups.var myEmailId = "s_c_bose@ina.com" var extractEmailIdRegEx = /(?:\w+)@(\w+).(?:\w+)/; var emailPart = myEmailId.match(extractEmailIdRegEx); console.log(emailPart); /* [ 0: "s_c_bose@ina.com" 1: "ina" index: 0 input: "s_c_bose@ina.com" groups: undefined length: 2 ] */

Quantifiers

As the name suggests it is used in regular expressions to specify the quantity or number of characters or expressions to match.

Below are the types of quantifiers we can use across regular expressions:

x*- This searches for the occurrence of the characterx0 or more times.x+- This searches for the occurrence of the characterx1 or more times.

This is the same as using the quantifier{1,}(See below).var str = "he saw a billllly goat"; var reg = /il*/; console.log(str.match(reg));// [ 'illlll', index: 10, input: 'he saw a billllly goat' ] reg = /il+/; console.log(str.match(reg));// [ 'illlll', index: 10, input: 'he saw a billllly goat' ]x?- This searches for the occurrence of the characterx0 or 1 time. Now when the previous quantifierx*orx+was used on the string, we saw the output matched all or the maximum number ofls present in the wordbillllly. It did not stop after finding the the first occurrence oflafter ani, but matched and showed all thels. This is the default behavior of the quantifiers*and+and this is called as greedy matching. To make it stop immediately after finding the first occurrence of alafter aniwe need to make it non-greedy. This is achieved by using?immediately after the quantifiers*or+. Why this works? By definition?returns a match if 0 or 1 matching characters are found and hence the match is returned immediately after it finds 1 character.var str = "he saw a billllly goat"; var reg = /il?/; console.log(str.match(reg));// [ 'il', index: 10, input: 'he saw a billllly goat' ] reg = /il+?/; console.log(str.match(reg));// [ 'il', index: 10, input: 'he saw a billllly goat' ]x{n}- This matches exactlynoccurrences of the characterx.nis a positive integer.x{n,}- This matches at leastnoccurrences ofx.nis a positive integer. Since no value is provided after the,it means we are not looking for any upper limit as to how many max matches can be possible.x{n,m}- This matches portions of string wheren <= count of(x) <= m

which means searches for the characterxif occurs at leastntimes and maximummtimes.nandmare both positive integers andm>n. So here both the lower and upper limit are provided and is a much stricter check.var str = "OMG! ghost ghooost ghoooooost ghooooooooooost" var reg = /o{1}/; console.log(str.match(reg));// [ 'o', index: 7, input: 'OMG! ghost ghooost ghoooooost ghooooooooooost' ] reg = /o{4}/; console.log(str.match(reg));// [ 'oooo', index: 21, input: 'OMG! ghost ghooost ghoooooost ghooooooooooost' ] reg =/o{9,}/; console.log(str.match(reg));// [ 'ooooooooooo', index: 32, input: 'OMG! ghost ghooost ghoooooost ghooooooooooost' ] reg = /o{1,3}/; console.log(str.match(reg));// [ 'o', index: 7, input: 'OMG! ghost ghooost ghoooooost ghooooooooooost' ]Unicode property escapes

This allows matching characters based on their Unicode properties.

To use this feature the flaguhas to be used which indicates the RegExp engine to treat it as a series of Unicode code points.

These can be used to match emojis, punctuation and letters from non-latin languages.

Characters are described by several properties which can of binary or non-binary types.

The syntax for matching non-binary values is :

The syntax for matching binary values is:\p{UnicodePropertyValue} \p{UnicodePropertyName=UnicodePropertyValue}

To apply negation of unicode value as a regular expression pattern the syntax is:\p{UnicodeBinaryPropertyName}

UnicodeBinaryPropertyName: Binary property names are listed here\P{UnicodePropertyValue} \P{UnicodePropertyBinaryName}

UnicodePropertyName: This includes the name of a non-binary property : General_Category(gc), Script(sc) or Script_Extensions(scx).

UnicodePropertyValue: A collection of token v A good description of unicode properties can be found herevar ustr = "like a 🤠"; var ureg = /\p{Emoji_Presentation}/gu; console.log(ustr.match(ureg)); /* [ 0: "🤠" length: 1 ] */

Script and Script Extension: Since every language uses different script when written e.g. English and Spanish are written in Latin whereas Macedonian, Mongolian, Bulgarian, Russian etc are written in Cyrillic.( Language and Script ).

For example if a string contains a mixture of Latin and Cyrillic characters then we can find for matches of a particular script type:var scstr = "НЕЛЛО РУССИА, Hello Russia"; var scregL = /\p{Script=Latin}/u; var scregC = /\p{Script=Cyrillic}/u; console.log(scstr.match(scregL)); /* [ 0: "H" index: 14 input: "НЕЛЛО РУССИА, Hello Russia" groups: undefined length: 1 ] */ console.log(scstr.match(scregC)); /* [ 0: "Н" index: 0 input: "НЕЛЛО РУССИА, Hello Russia" groups: undefined length: 1 ] */

So that was a brief explanations of Regular Expressions in JavaScript. There are the elements and using these more complex and useful regular expressions can be written for various use cases. However one thing to always keep in mind is that regular expression if not written optimally can result in severe performance toll.

We will some more interesting features in our upcoming posts.

References:

MDN - Regular Expressions

Groups and Ranges

Regular Expressions CheatSheet

https://regex101.com/

http://regviz.org/

https://www.rexegg.com/regex-capture.html